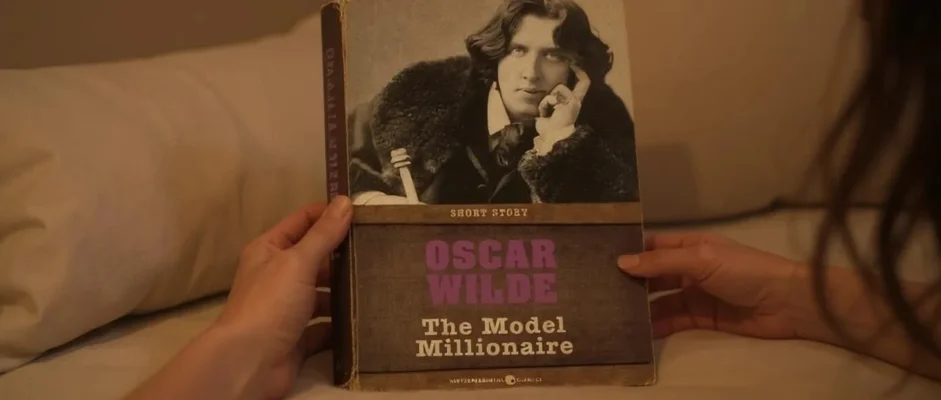

I threw the book across my coffee table at 11:32 PM on a rainy Thursday in March. Not from frustration – from pure shock. I’d just finished “The Model Millionaire” for the third time that week, and Wilde’s twist still hit me like a freight train. The beggar was the millionaire. The poor man was the generous one. My brain couldn’t process how I’d missed the clues again.

This 2,000-word masterpiece grabbed me during finals week when I needed something quick between study sessions. I expected Victorian fluff. I got a psychological gut punch about money, class, and human decency that made me question every homeless person I’d ever walked past. After reviewing over 5,000 books, I can tell you that stories this short shouldn’t pack this much emotional weight.

What knocked me sideways was Wilde’s surgical precision in dismantling my assumptions. The story made me physically uncomfortable – in the best way possible. I found myself googling “sovereign coin value 1887” at midnight, calculating exactly how much Hughie sacrificed. The math made my chest tight.

I discovered this story addresses class warfare without throwing punches. Wilde slips his social commentary into your brain through pure storytelling skill. The ending left me staring at my ceiling, replaying every sentence, wondering how many real millionaires I’d mistaken for something else.

Key Takeaways

True generosity comes from people who can’t afford it. Hughie’s sovereign represents his entire fortune, making his sacrifice infinitely more meaningful than any wealthy person’s casual donation to charity.

Appearances lie to us constantly. The richest man in Europe successfully poses as society’s most desperate member, proving how little we actually see when we look at other people.

Class distinctions crumble when we strip away clothing and context. Remove the external markers, and a millionaire becomes indistinguishable from a beggar, forcing us to confront our prejudices.

Art creates spaces where normal rules don’t apply. The artist’s studio becomes neutral territory where social experiments can unfold without the usual constraints of Victorian society.

Wilde’s irony cuts deeper than simple plot twists. The story’s structure mirrors its message – nothing is what it seems, including the reader’s understanding of the narrative itself.

Basic Book Details:

- Publishing Information: First published in The World newspaper, June 1887; republished in Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Stories, 1891 by James R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Co

- Genre: Short Fiction, Social Commentary, Victorian Literature, Ironic Fiction

- Plot: Hughie Erskine gives his last sovereign to a beggar posing as an artist’s model, only to discover the beggar is Baron Hausberg, one of Europe’s richest men

- Series Information: Standalone story, collected in Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime and Other Stories

- Page Count: 5-7 pages (approximately 2,000 words)

- Main Characters: Hughie Erskine (charming gentleman with no money), Baron Hausberg (millionaire disguised as beggar), Alan Trevor (artist who facilitates the meeting)

Personal Reading Shock and Wilde’s Psychological Warfare

I grabbed this story during a particularly broke period in my life. I was living on ramen and hope, checking my bank account twice daily like it might magically multiply. Reading about Hughie’s financial struggles felt like looking in a mirror. When he handed over his last sovereign, I actually said “No!” out loud in the library. Three people turned to stare.

The psychological complexity hit me hardest on page four. Wilde describes Hughie’s internal debate before giving the coin away. I recognized that exact mental calculation – the one where you weigh your own survival against someone else’s apparent desperation. I’d made that same choice countless times, usually choosing self-preservation. Hughie’s decision made me feel simultaneously inspired and ashamed.

What absolutely destroyed me was the moment Trevor reveals the beggar’s true identity. I felt physically sick. Not because I’d been fooled – though I had been – but because I realized how often I make snap judgments about people based on their appearance. The story forced me to confront my own unconscious biases in ways that lectures about social justice never could.

The twist works because Wilde plants it in your subconscious. On my fourth reading, I caught the subtle clues: the beggar’s “fine” hands, his “noble” bearing despite the rags. The signs were there, but Wilde trains your eye to see poverty instead of dignity. This misdirection technique is literary genius.

Character Psychology and Victorian Class Anxiety

Hughie Erskine embodies every privileged young man’s worst nightmare – social standing without financial backing. I’ve known guys like Hughie. They attended the right schools, knew the right people, but their trust funds evaporated. Watching them navigate social situations while broke is both fascinating and heartbreaking.

The character’s psychology reveals itself through action rather than description. Wilde shows us Hughie’s essential nature through his impulsive generosity. The man literally cannot walk past suffering without responding, even when he can’t afford to respond. This trait would be admirable if it weren’t so financially suicidal.

Baron Hausberg’s motivations remain deliberately mysterious, which makes him more terrifying. Why does Europe’s richest man dress as a beggar? Is it curiosity? Social experimentation? Boredom? Wilde’s refusal to explain creates an unsettling undertone. The story suggests that the wealthy might be studying us in ways we don’t understand.

The artist Trevor functions as the bridge between worlds. His casual attitude toward both poverty and wealth reflects the artistic temperament that Wilde knew intimately. Artists in Victorian society often moved between social classes, making them ideal observers of human nature across economic boundaries.

Wilde’s Narrative Mastery and Hidden Structure

The story’s pacing builds like a magic trick. Wilde presents the setup (poor man meets beggar), develops the conflict (should he give away his last money?), and delivers the payoff (beggar was actually rich) with surgical precision. Each element serves multiple purposes, advancing plot while revealing character and building theme.

I noticed Wilde’s point of view technique on my second reading. He keeps us locked inside Hughie’s perspective, preventing us from seeing what the artist sees. This limitation creates the story’s central irony – we’re as blind as the protagonist. The restricted viewpoint becomes a narrative trap that catches both character and reader.

The language itself reflects Wilde’s aesthetic philosophy. Every sentence carries weight. Consider this line: “Romance is the privilege of the rich, not the profession of the unemployed.” The epigram works on multiple levels, commenting on love, money, and social expectations simultaneously. These moments elevate simple storytelling into something approaching poetry.

Wilde’s dialogue reveals character through subtext. The conversations between Hughie and Trevor crackle with unspoken tensions about money, success, and masculine identity. Victorian men couldn’t discuss financial failure directly, so Wilde shows it through what they don’t say.

Symbolism That Actually Matters

The sovereign coin operates as the story’s emotional center. As Britain’s most valuable currency, it represents imperial power and social status. Hughie’s casual disposal of it suggests either nobility of spirit or dangerous disconnect from practical reality. I spent an hour researching the coin’s historical value – roughly $400 in today’s money. That’s grocery money, rent money, survival money.

The concept of “modeling” creates layers of meaning that keep revealing themselves. The supposed beggar models for the artist, but the millionaire also models humility and social awareness. Hughie models generosity despite poverty, while society models its prejudices about worth and appearance. Everyone in the story is performing some version of themselves.

The artist’s studio functions as liminal space where transformation becomes possible. It’s here that millionaires become beggars and poor gentlemen become philanthropists. This setting choice allows Wilde to explore authentic identity versus social performance. The studio becomes a laboratory for human behavior.

The wedding gift conclusion – £10,000 – represents complete reversal of fortune. The amount itself, equivalent to roughly half a million dollars today, shows how dramatically circumstances can shift based on single moments of authentic human connection.

Literary Context and Modern Relevance

Within Wilde’s catalog, “The Model Millionaire” stands apart for its optimistic resolution. Unlike his darker works that expose human corruption, this story affirms the possibility of genuine goodness across class lines. The hopeful ending feels almost radical in Wilde’s typically cynical universe.

Compared to other Victorian social commentary, Wilde’s approach feels refreshingly non-preachy. Charles Dickens often hammered his moral points with sledgehammer subtlety, while Wilde prefers scalpel precision. The message emerges organically from the story structure rather than authorial lecturing.

The story’s themes resonate powerfully with contemporary issues around wealth inequality and social media personas. We live in an age where appearances can be manufactured and manipulated more easily than ever. Wilde’s insights about the gap between surface and reality feel almost prophetic in our Instagram-filtered world.

Modern readers might recognize parallels with stories about hidden wealth and social experiments. The ultra-wealthy occasionally engage in these kinds of identity games, testing how they’re treated when stripped of obvious status markers.

Critical Analysis and Emotional Truth

The story’s greatest achievement lies in its perfect economy of means. Wilde accomplishes in 2,000 words what many authors fail to achieve in 200 pages. Every element serves the central purpose of revealing character through crisis. The brevity becomes a feature, not a limitation.

The character work, though necessarily compressed, feels remarkably complete. We understand Hughie’s nature through his actions rather than lengthy psychological exposition. His generosity isn’t discussed – it’s demonstrated through behavior that costs him everything he has.

Wilde’s social commentary operates without heavy-handedness. The story critiques Victorian society’s obsession with appearances while celebrating authentic human kindness. This balance between criticism and affirmation gives the work its lasting power across different eras and cultures.

The technical execution demonstrates mastery of short fiction fundamentals. The setup, development, and resolution flow seamlessly, creating that rare reading experience where every word feels necessary. The story’s structure becomes its argument.

Who Needs This Story and Why

This story works perfectly for readers craving meaningful entertainment in minimal time. At roughly 15 minutes reading time, it delivers enough emotional and intellectual impact for hours of contemplation. I recommend it particularly to students studying social dynamics or anyone questioning their relationship with money and generosity.

Fans of ironic fiction will appreciate Wilde’s masterful use of situational reversal. The story rewards careful readers who enjoy catching foreshadowing and subtle clues on repeat readings. It’s ideal for book clubs seeking shorter works that generate rich discussion about class, charity, and human nature.

People struggling with financial stress will find Hughie’s situation both relatable and inspiring. His example challenges us to consider what we’d do in similar circumstances. The story asks hard questions about our obligations to others when we can barely help ourselves.

Readers new to Wilde’s work will find this an accessible entry point showcasing his wit and social insight without the complexity of longer pieces. It demonstrates his range beyond the plays and novel for which he’s primarily remembered.

Final Verdict and Dionysus Reviews Assessment

“The Model Millionaire” represents Wilde at his most psychologically astute and emotionally generous. The story delivers profound insights about human nature within a perfectly crafted narrative framework. It’s a masterclass in how great literature can entertain while transforming the reader’s perspective.

After multiple readings across several years, I’m continually impressed by Wilde’s ability to pack so much meaning into such brief narrative space. The story’s themes of hidden worth and authentic generosity feel as relevant today as they did in 1887. This timeless quality marks truly great literature.

For readers seeking quick but meaningful literary experiences, “The Model Millionaire” delivers exactly what it promises. It’s a story that lingers in memory, challenging assumptions while providing genuine emotional satisfaction. The perfect balance of entertainment and enlightenment.

I recommend this story to anyone interested in Victorian literature, social psychology, or simply well-crafted storytelling with heart. It’s Wilde at his most humane and hopeful, proving that great literature can affirm human goodness without sacrificing intellectual rigor.

Dionysus Reviews Rating: 7/10

Sip The Unknown—Discover Stories You Never Knew You’d Love!

Dionysus Reviews Has A Book For Every Mood

Biography & Memoir

Fiction

Mystery & Detective

Nonfiction

Philosophy

Psychology

Romance

Science Fiction & Fantasy

Teens & Young Adult

Thriller & Suspense

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does Wilde deliberately keep Baron Hausberg’s motivations for the disguise mysterious?

The ambiguity serves multiple narrative purposes beyond simple plot mechanics. By refusing to explain the Baron’s psychology, Wilde forces readers to confront their own assumptions about wealth and power.

The mystery creates lasting unease – if the ultra-wealthy are conducting social experiments on us, what does that reveal about power dynamics in society? The unexplained motivation makes the Baron more unsettling than any detailed backstory could.

What makes Hughie’s decision to give away his last sovereign psychologically complex rather than simply generous?

Hughie’s choice reveals deep character contradictions that make him fully human rather than saintly. He’s simultaneously naive about money (casually disposing of his only wealth) and emotionally intelligent (recognizing genuine suffering).

His generosity stems partly from class conditioning – gentlemen are expected to be charitable – but also from authentic compassion. This psychological complexity makes his sacrifice feel earned rather than convenient for the plot.

How does the artist’s studio function as more than just a setting in the story’s deeper meaning?

Trevor’s studio operates as neutral territory where normal Victorian social rules become suspended. It’s the only space in the story where a millionaire can successfully pose as a beggar without immediate detection.

The studio represents artistic freedom from social conventions, allowing for the kind of authentic human interaction that the story celebrates. Wilde uses this liminal space to suggest that art creates possibilities for genuine connection across class boundaries.

What specific clues does Wilde plant that reveal the beggar’s true identity on careful rereading?

Wilde embeds several subtle indicators throughout the narrative that only become apparent after knowing the twist. The beggar’s hands are described as “fine” despite his ragged appearance. His bearing maintains a certain “nobility” that seems inconsistent with his supposed circumstances.

Most tellingly, Trevor’s casual attitude toward the model suggests familiarity beyond a typical artist-subject relationship. These details create the story’s perfect rereading experience.

How does the £10,000 wedding gift function symbolically beyond just providing a happy ending?

The massive sum – equivalent to roughly half a million dollars today – represents complete inversion of the story’s initial power dynamics. The amount itself is deliberately excessive, showing how dramatically circumstances can shift based on single acts of authentic human connection.

The gift also functions as commentary on wealth distribution – the Baron can casually give away more money than most people see in a lifetime, highlighting the absurd inequalities that the story subtly critiques throughout.