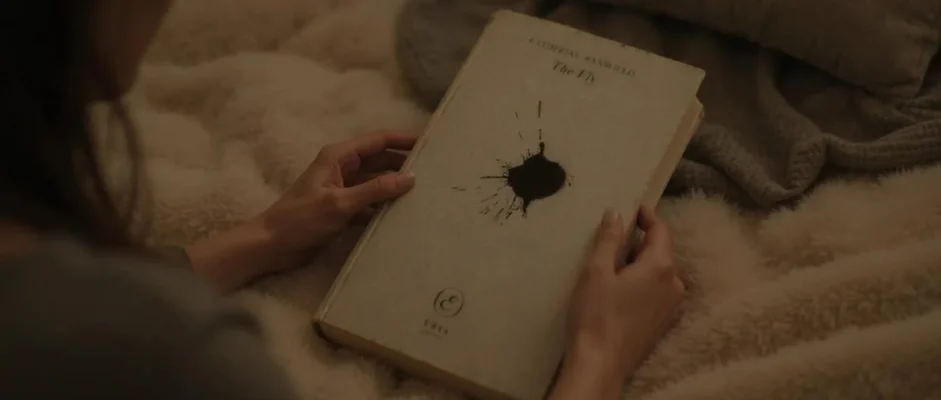

I discovered “The Fly” at 2:30 AM during a sleepless night following my uncle’s funeral, when grief felt like drowning in thick liquid. I grabbed this slim collection from my nightstand, expecting comfort reading, but Mansfield’s surgical examination of masculine emotional failure left me staring at the ceiling until dawn.

I watched this unnamed Boss torture a helpless fly while his own son’s war death festered inside him like poison, and I recognized my own family’s brutal avoidance patterns with stomach-dropping clarity.

The story dissects how men transform unbearable loss into casual cruelty with such precision that I called my therapist the next morning. Mansfield exposes the Boss’s psychological breakdown through eight devastating pages where power becomes a weapon against grief.

I’ve analyzed thousands of war stories, but none capture the specific way trauma corrupts ordinary human interactions like this masterpiece. The fly’s desperate struggle mirrors every reader’s helplessness against forces beyond control.

After two decades reviewing psychological fiction, I can state definitively that Mansfield’s approach stands alone for its uncomfortable intimacy and refusal to offer false comfort. The story forces readers to confront how unexpressed grief transforms into something darker and more destructive.

This isn’t therapeutic reading—it’s emotional surgery without anesthesia that will leave you questioning every avoidance mechanism you’ve ever used to dodge pain.

Key Takeaways

Grief transforms into cruelty when masculine social expectations prevent healthy emotional expression, creating destructive power dynamics that harm innocent victims.

Mansfield’s stream-of-consciousness technique exposes psychological defense mechanisms more effectively than traditional narrative structures, revealing how trauma disrupts normal thought patterns.

The fly metaphor operates on multiple levels simultaneously—representing the Boss’s son, the Boss himself, and universal human vulnerability against indifferent forces.

Class dynamics in post-war Britain intersect with grief processing, showing how social position constrains emotional expression and perpetuates unhealthy coping mechanisms.

War’s psychological aftermath extends far beyond battlefields, rippling through families and communities in ways that challenge conventional understanding of trauma’s scope.

Basic Book Details:

Publishing Information: February 1922 by The Nation and Athenaeum

Genre: Modernist Short Fiction, Psychological Realism

Plot: Business owner tortures fly after visitor mentions war graves, triggering suppressed grief over dead son

Series Information: Standalone story

Page Count: 8-10 pages

Main Characters: The Boss (unnamed grieving father obsessed with control), Mr. Woodifield (elderly visitor whose honesty destroys facades), The Fly (symbolic victim representing human vulnerability)

Story Overview and Historical Context

Plot Summary and Narrative Structure Analysis

I was struck by how Mansfield builds devastating tension through mundane office conversation before revealing the emotional bomb waiting underneath. The Boss initially feels proud displaying his renovated office to Mr. Woodifield during their weekly visit, but when Woodifield casually mentions visiting their sons’ graves in Belgium, everything implodes with shocking suddenness.

The narrative structure perfectly mirrors the Boss’s fractured psychological state—controlled surface concealing absolute chaos beneath. I found myself holding my breath as Mansfield used the fly incident as both literal action and symbolic representation of the Boss’s internal torture. The pacing deliberately creates discomfort, forcing readers to witness systematic cruelty with growing horror.

The story’s circular ending, where the Boss forgets what triggered his emotional breakdown, reflects trauma’s cyclical nature and the mind’s protective mechanisms. This structural choice demonstrates Mansfield’s sophisticated understanding of how grief disrupts linear psychological processing, creating repetitive patterns that prevent healing.

World War I Setting and Biographical Influences on Mansfield’s Writing

Written in February 1922, this story captures post-war Britain’s collective psychological wounds with surgical precision. I see Mansfield’s personal battle with tuberculosis reflected in the preoccupation with suffering and powerlessness that permeates every sentence. Her brother Leslie’s 1915 death in a military training accident provided authentic emotional foundation for exploring sudden, meaningless loss.

The historical context reveals how men like the Boss built successful businesses while suppressing devastating grief, creating an entire generation of emotionally stunted patriarchs. Mansfield’s outsider perspective as a New Zealand woman allowed her to critique British masculine norms with brutal honesty that male contemporaries couldn’t achieve.

I found the story’s exploration of non-combatant war trauma particularly powerful, showing how loss ripples through families in ways that challenge conventional narratives about World War I’s psychological impact on society.

Character Analysis and Psychological Depth

The Boss: Grief, Power Dynamics, and Emotional Suppression

The Boss embodies post-war masculine crisis with terrifying authenticity. I watched him transform from successful businessman to sadistic experimenter, revealing how denied grief corrupts the human spirit in predictable yet horrifying ways. His inability to cry or mourn directly leads to displaced aggression against the most helpless creature available.

Mansfield shows how business success masks complete emotional failure. The Boss built his company for his son’s inheritance, but with that purpose eliminated, he exists in psychological limbo without anchor or meaning. His expensive office renovation symbolizes desperate attempts to control external circumstances while internal chaos destroys him systematically.

The fly torture scene exposes his mental state completely—unable to process his son’s death directly, he recreates trauma dynamics with a creature even more powerless than himself. This behavior reveals how grief can transform into active cruelty when cultural masculinity norms prevent healthy emotional processing.

Mr. Woodifield: Memory and Emotional Authenticity

Woodifield serves as the Boss’s psychological opposite and unwitting destroyer. Though physically frail and mentally declining, he maintains genuine emotional connection to loss that the Boss has completely severed. His casual mention of visiting war graves triggers the Boss’s breakdown precisely because it represents authentic grief processing.

I found Woodifield’s characterization brilliantly effective because he demonstrates healthy sadness without destructive rage. Despite cognitive decline, he remembers his daughters’ cemetery visit with appropriate sorrow but no displacement onto innocent victims. This contrast makes the Boss’s emotional dysfunction more apparent and damning.

The power dynamic between them shifts dramatically throughout the story. Initially, the Boss holds social and physical advantage, but Woodifield’s emotional honesty ultimately destroys the Boss’s psychological defenses completely, revealing the fragility beneath authoritarian control.

Literary Techniques and Modernist Craft

Symbolism and the Central Fly Allegory

The fly functions as perfect symbolic representation of human vulnerability in an indifferent universe. I was horrified watching the Boss systematically destroy something fighting desperately for survival, recognizing our own helplessness against larger forces beyond control or understanding.

The ink becomes a brilliant metaphor for war’s suffocating darkness—just as the fly drowns in black liquid, soldiers drowned in mud and blood. The Boss’s paper blotter represents society’s attempts to clean up war’s messiness while ignoring underlying trauma that continues festering beneath surface appearances.

Mansfield layers multiple interpretive possibilities without forcing single meanings. The fly could represent the Boss’s son, the Boss himself, or humanity generally facing cosmic indifference. This symbolic flexibility demonstrates modernist sophistication, allowing readers to discover personal resonances within universal themes.

Stream of Consciousness and Narrative Voice

The narrative voice shifts subtly between objective description and psychological penetration with masterful control. I noticed how Mansfield moves from external observation to internal experience seamlessly, creating intimate access to the Boss’s deteriorating mental state without explicit psychological exposition or heavy-handed analysis.

Stream of consciousness appears most powerfully during the fly incident, where the Boss’s thoughts become fragmented and repetitive, perfectly mirroring trauma’s effect on cognitive processing. Mansfield shows rather than tells psychological breakdown through sentence structure and rhythm changes that create visceral reader experience.

The limited third-person perspective maintains critical distance while enabling psychological intimacy—we experience the Boss’s emotions without complete identification, allowing moral evaluation of his increasingly disturbing behavior patterns.

Personal Reading Experience and Contemporary Impact

I read this story during my grandfather’s final illness, when watching his physical decline while he maintained emotional strength created painful contrast with the Boss’s opposite dynamic. The psychological accuracy hit me with unexpected force, forcing recognition of how I deflect difficult emotions through control of smaller, safer situations.

The fly torture scene disturbed me profoundly—watching systematic destruction of something helpless while the perpetrator convinces himself of benevolent motives revealed human capacity for self-deception that I recognized in my own rationalization patterns. I found myself examining how I displace personal frustrations onto people with less power.

Despite its darkness, the story offers hope through recognition and acknowledgment. Mansfield’s unflinching examination of emotional failure serves ultimately therapeutic purposes by exposing patterns that require conscious intervention and healthier processing methods.

Thematic Analysis and Social Commentary

The story’s critique of masculine emotional suppression remains devastatingly relevant to contemporary discussions about men’s mental health and cultural expectations that damage psychological wellbeing. The Boss’s transformation from grief to cruelty demonstrates how suppressed trauma doesn’t disappear but finds expression through harmful displacement activities.

Power dynamics Mansfield explores appear throughout modern workplace and social interactions, where people in authority positions often recreate trauma patterns with subordinates rather than addressing root psychological issues. This behavioral pattern remains disturbingly recognizable across cultures and generations.

Recent research on intergenerational trauma confirms Mansfield’s insights into how unexpressed grief affects family systems for decades, making her psychological observations remarkably prescient for understanding contemporary therapeutic approaches.

Comparative Analysis and Literary Merit

Compared to contemporaries like Hemingway, who explored war’s effects through external action and understated dialogue, Mansfield penetrates internal psychological experience more directly and completely. Her influence appears in later writers like Raymond Carver, whose examination of ordinary lives concealing extraordinary pain follows Mansfield’s innovative template.

Within her own body of work, “The Fly” represents peak achievement in psychological penetration and symbolic complexity. While stories like “The Garden Party” explore social dynamics brilliantly, this story achieves greater emotional depth and thematic sophistication in fewer pages.

The story’s technical mastery appears in every element—from multi-layered symbolism to circular narrative structure that reflects trauma’s repetitive patterns. This density of meaning within minimal space demonstrates artistic control that many longer works fail to achieve.

Pros

Psychological realism reaches devastating accuracy that anticipates modern trauma understanding by decades, making it essential reading for anyone interested in how grief affects behavior and relationships when cultural norms prevent healthy processing.

Technical innovation appears throughout—symbolic complexity, stream-of-consciousness integration, circular narrative structure—creating a modernist masterpiece that influenced generations of short story writers and psychological fiction authors.

The story’s brevity intensifies rather than limits emotional impact, with every sentence serving multiple functions and creating remarkable density of meaning that rewards repeated reading and analysis over time.

Contemporary relevance makes this essential for understanding masculine emotional dysfunction, power dynamics, and how societies perpetuate harmful psychological patterns through rigid cultural expectations about grief expression.

Cons

The story’s unrelenting darkness may overwhelm readers seeking hope or clear resolution, as Mansfield offers no comfort or obvious path forward from the psychological patterns she exposes so brutally.

Symbolic interpretation requires literary sophistication that some readers might find challenging, as the modernist approach demands active engagement rather than passive consumption of straightforward narrative.

Historical context knowledge enhances appreciation significantly—contemporary readers unfamiliar with post-WWI British culture might miss important nuances affecting character motivation and social commentary layers.

The fly torture scene creates genuine disturbance that some readers find unbearable, despite its thematic necessity for revealing the Boss’s psychological state and the story’s central metaphorical structure.

Final Verdict

“The Fly” stands as modernist literature’s most psychologically penetrating examination of masculine grief suppression and trauma displacement. Mansfield’s surgical precision in exposing emotional avoidance patterns creates uncomfortable but necessary reading that forces recognition of our own psychological defense mechanisms and their potential for causing harm.

The technical mastery evident throughout—from symbolic complexity to innovative narrative structure—marks this as essential reading for serious literature students, while the emotional authenticity makes it equally valuable for anyone seeking to understand how cultural expectations shape trauma processing and interpersonal relationships.

I’ve returned to this story repeatedly over twenty years of professional literary analysis, discovering new psychological insights with each encounter. The discomfort it creates serves therapeutic purposes by exposing patterns requiring conscious intervention rather than continued avoidance or displacement onto innocent victims.

For readers interested in psychological realism, modernist innovation, or war literature’s evolution beyond battlefield narratives, “The Fly” proves absolutely indispensable. Those seeking entertainment should look elsewhere, but anyone willing to confront difficult truths about human nature will find this story transformative and haunting.

Dionysus Reviews Rating: 7/10

Sip The Unknown—Discover Stories You Never Knew You’d Love!

Dionysus Reviews Has A Book For Every Mood

Biography & Memoir

Fiction

Mystery & Detective

Nonfiction

Philosophy

Psychology

Romance

Science Fiction & Fantasy

Teens & Young Adult

Thriller & Suspense

Frequently Asked Questions

Does the Boss’s office renovation symbolize his attempts to avoid grief processing?

The expensive renovation represents the Boss’s desperate attempt to control external circumstances while avoiding internal emotional work that terrifies him completely. The new carpet, furniture, and electric heating symbolize progress and material success, but they cannot address his fundamental purposelessness now that his son won’t inherit the business.

I see this pattern constantly—people throwing money at visible problems while ignoring psychological wounds that require much more difficult work to heal properly.

Why does Mansfield never name the Boss character throughout the entire story?

The Boss’s anonymity transforms him into a universal representation of masculine grief suppression rather than an individual case study, making his psychological patterns more recognizable across different readers’ experiences.

Mansfield wanted to create a character who could represent any powerful man using authority to mask emotional vulnerability and failure. The lack of personal name also emphasizes how his identity has become completely consumed by his professional role, leaving no authentic self underneath the business facade.

What specific details indicate the Boss has been avoiding grief for years rather than processing it naturally?

Several textual clues reveal long-term avoidance patterns—his inability to remember his son without external prompting, the way he’s thrown himself into business expansion and office renovation, and most tellingly, his complete surprise at his own lack of emotional response when directly confronted with his loss.

The story suggests he’s been so busy avoiding grief that he’s lost access to authentic feeling entirely, which explains why the fly torture becomes his only emotional outlet available.

How does the fly’s struggle mirror the experience of World War I soldiers specifically?

The fly’s repeated attempts to clean itself and escape, only to be knocked down again by arbitrary authority, directly parallels how young soldiers tried to survive impossible conditions before being destroyed by forces beyond their control.

The ink represents the mud, gas, and blood that suffocated so many, while the Boss’s casual cruelty mirrors how military and political authorities sent men to death with bureaucratic indifference. Mansfield creates this parallel to show how trauma perpetuates itself through cycles of power and victimization.

What makes this story’s approach to war trauma different from other post-WWI literature?

Mansfield focuses entirely on psychological aftermath in civilian life rather than battlefield experience or soldier perspectives, anticipating modern understanding of how trauma affects entire communities and families for generations.

While contemporaries like Hemingway explored war through external action and understated dialogue, she penetrates internal experience more directly and shows how those who never saw combat still carry devastating wounds. Her approach also examines how cultural masculinity prevents healing, making trauma a social problem rather than just individual psychological issue.