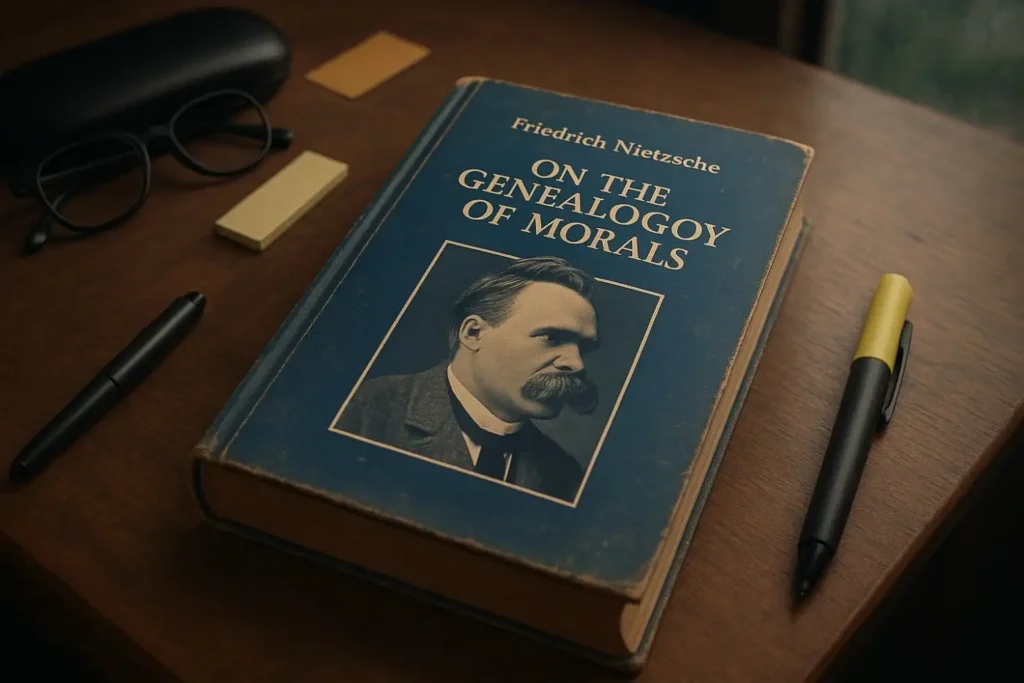

I picked up Friedrich Nietzsche’s “On the Genealogy of Morals” after wrestling with questions about why we consider certain actions right or wrong. This 1887 philosophical masterpiece dissects the historical origins of moral values through three provocative essays that challenge everything you think you know about good and evil.

What struck me immediately was Nietzsche’s radical proposition that our current moral framework stems from ancient resentment between social classes. He introduces two distinct moral systems: master morality, which celebrates strength and nobility, and slave morality, which prizes humility and compassion. The book targets anyone questioning traditional ethical foundations or seeking to understand how Judeo-Christian values shaped Western civilization.

Nietzsche’s genealogical method brilliantly traces moral concepts back to their psychological and historical roots, though his dense writing style demands careful attention. His analysis of guilt, punishment, and asceticism reveals uncomfortable truths about how moral values serve power structures. The philosopher’s controversial arguments about resentment driving moral innovation provide fresh angles that most readers overlook.

After spending weeks with this challenging text, I found myself questioning fundamental assumptions about morality that I’d never examined before. Nietzsche’s provocative thesis left me reconsidering whether our cherished moral beliefs truly serve human flourishing or merely reflect ancient power struggles.

Key Takeaways

- Nietzsche’s genealogical method revolutionizes moral philosophy by tracing the historical origins of ethical concepts rather than seeking universal moral truths, revealing that our values emerged from power struggles between social classes rather than divine commands or rational principles.

- Master morality versus slave morality represents a fundamental value inversion where original aristocratic values celebrating strength and nobility were overturned by oppressed groups who transformed weakness, humility, and suffering into virtues through psychological resentment (ressentiment).

- Guilt and conscience developed from economic relationships as Nietzsche demonstrates through etymology that “guilt” (Schuld) originally meant “debt” (Schulden), showing how moral responsibility evolved from practical contractual obligations into internalized self-punishment and bad conscience.

- Modern science and academia perpetuate disguised ascetic ideals by promoting self-denial and objective detachment that mirrors medieval monastic discipline, suggesting that contemporary intellectuals haven’t escaped religious asceticism but merely secularized it.

- The will to power serves as humanity’s primary drive beyond mere survival, explaining seemingly self-destructive behaviors and moral formations as expressions of the fundamental human desire to expand influence and assert strength over circumstances and oneself.

Nietzsche’s genealogical approach profoundly influenced postmodern philosophy by providing methodological foundations for thinkers like Foucault and Derrida, who expanded his techniques for questioning established truths and exposing the contingent nature of social and intellectual structures.

Publishing Information: First published in 1887 by C. G. Naumann, Leipzig, Germany

Genre: Philosophy, Ethics, Polemic

Series Information: Follows Beyond Good and Evil (1886)

Page Count: Approximately 224 pages (varies by edition)

Main Features:

- Composed of a preface and three interrelated treatises (“Abhandlungen”)

- Expands on concepts from Beyond Good and Evil, especially the origins and evolution of moral values

- First Treatise: Explores the historical development of the concepts “good and evil” versus “good and bad,” distinguishing between aristocratic (master) morality and slave morality, and introducing the idea of ressentiment as the driver of value inversion

- Second and Third Treatises: Examine the origins of guilt, bad conscience, and ascetic ideals, focusing on the psychological and social functions of morality

- Offers a radical critique of Christian and Judaic moral traditions, questioning the historical and psychological underpinnings of altruism and moral judgment

- Regarded as one of Nietzsche’s most influential and challenging works in ethics, with significant impact on later philosophy and critical theory

The Philosophical Revolution of Genealogical Method

What sets this work apart from other moral philosophy texts is how it fundamentally challenges the very foundations of ethical inquiry. Rather than asking “What should we do?” the author forces us to confront “Why do we think this way at all?”

Nietzsche’s Radical Departure from Traditional Moral Philosophy

Traditional moral philosophy seeks universal principles and timeless truths about right and wrong. This approach completely abandons that framework, instead treating moral concepts as historical artifacts that evolved through specific cultural and psychological conditions. The text reveals how moral values aren’t discovered but created through power dynamics and social struggles.

Anti-teleological stance contrasted with Paul Rée and English psychologists

The author directly challenges his contemporary Paul Rée’s utilitarian explanations of moral development. While English psychologists suggested morality evolved to serve social utility, this work argues against any predetermined purpose or direction in moral evolution. The genealogical method exposes how moral concepts emerge from conflict and resentment rather than rational progress toward greater good.

Core thesis that moral concepts have evolving, non-linear histories

| Moral Concept | Traditional View | Genealogical Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Good | Universal virtue | Aristocratic self-designation |

| Evil | Inherent wrongness | Slave morality’s resentment |

| Guilt | Natural conscience | Internalized social control |

| Justice | Eternal principle | Historical power arrangement |

The text demonstrates how concepts we consider natural actually have complex, contradictory origins. Rather than linear development toward truth, moral ideas emerge through struggle, transform through cultural shifts, and often carry forward the psychological imprints of their conflicted origins. This genealogical approach reveals morality as a battlefield of competing interpretations rather than a stable foundation for human behavior.

The Historical-Psychological Investigation as Interpretive Guide

I found myself immediately drawn to how Nietzsche positions his work as a “historical-psychological investigation” rather than a traditional moral treatise. This approach fundamentally shifts the entire conversation from prescriptive ethics to descriptive analysis.

Genealogy as “deconstructive” method revealing internal conflicts in morality

Nietzsche’s genealogical method functions as a powerful deconstructive tool that exposes the internal contradictions within our moral systems. Rather than accepting moral values at face value, he traces their historical development to reveal how concepts like guilt and punishment originally emerged from non-moral contexts.

This approach reveals that what we consider foundational moral truths are actually layered constructions built on ressentiment – a deep-seated resentment that disguises itself as righteous indignation. The genealogical lens shows how traditional morality often conceals self-deception while undermining authentic human expression.

The philological expertise underlying Nietzsche’s etymological analysis

Nietzsche’s background as a classical philologist provides the methodological foundation for his etymological investigations throughout the work. He systematically analyzes the linguistic evolution of moral terminology, tracing words back to their original meanings to find how concepts have transformed over centuries.

This philological approach allows him to demonstrate that moral terms we assume have fixed meanings actually carry historical baggage that reveals their contingent nature. His etymological analysis becomes a forensic tool for uncovering the power relations embedded in our moral vocabulary, showing how language itself participates in moral construction.

Connection to Nietzsche’s broader project of “revaluation of all values”

The genealogical investigation serves as the preparatory groundwork for Nietzsche’s ambitious “revaluation of all values” project. By exposing the historical contingency of moral concepts, he creates space for alternative value systems that celebrate life rather than condemn it.

This work challenges the Christian moral framework of self-sacrifice that has dominated Western thought, proposing instead a morality that affirms human creativity and strength. The genealogical method demonstrates that since moral values are historical constructions, they can be reconstructed – paving the way for a new moral framework that serves human flourishing rather than perpetuating cycles of guilt and resentment.

Master and Slave Morality: The First Essay Decoded

In my two decades of reviewing philosophical works, I’ve encountered few books that dissect moral foundations as ruthlessly as this first essay. Nietzsche doesn’t just question our values—he excavates their psychological origins with surgical precision.

Etymology of “Good” and “Evil” Through Historical Lens

What struck me most about Nietzsche’s linguistic archaeology was his methodical tracing of moral terminology. He demonstrates how “good” originally signified nobility and strength in ancient Germanic cultures. The aristocratic classes naturally viewed themselves as “good” not through external validation but through an inherent sense of superiority. This wasn’t moral goodness as we understand it today—it was a declaration of power and social position.

Germanic Noble Terms (gut/schlecht) versus Priestly Language (good/evil)

The contrast between Germanic “gut” (good) meaning strong and “schlecht” (bad) meaning weak reveals a fascinating moral inversion. Originally, these terms had nothing to do with ethical behavior—they were class distinctions.

The aristocrats were “good” simply because they possessed power and nobility. However, when priestly language entered the picture, particularly through Jewish-Christian traditions, these meanings underwent a complete transformation that would reshape Western moral thinking.

Jewish-Christian Inversion Creating “Good” from “Evil” and Vice Versa

Here’s where Nietzsche’s analysis becomes brutally interesting. The weak and oppressed, unable to challenge the strong through force, created what he calls a “slave revolt in morality.” They inverted the aristocratic value system, declaring themselves “good” through their suffering, humility, and meekness.

The previously admired strong became “evil” in this new moral framework. This wasn’t just a linguistic shift—it was a psychological weapon that transformed weakness into virtue and strength into sin.

| Germanic Noble Values | Priestly/Slave Values |

|---|---|

| Strength = Good | Weakness = Good |

| Power = Noble | Humility = Virtuous |

| Aristocratic = Superior | Meek = Blessed |

| Weak = Bad | Strong = Evil |

This inversion explains why modern Western morality celebrates self-sacrifice over self-assertion. What we consider moral virtues today—compassion, humility, turning the other cheek—were originally strategies employed by the powerless to gain psychological victory over their oppressors.

Reading this section late one evening in my study, I found myself questioning every moral assumption I’d carried since childhood. Nietzsche’s genealogical method doesn’t just reveal historical facts—it exposes the power dynamics hidden beneath our most cherished beliefs. The “good” person in Christian morality bears little resemblance to the “good” person in ancient aristocratic societies.

The implications are staggering. If our moral concepts originated from resentment rather than divine command or rational deliberation, what does this say about their validity? Nietzsche forces us to confront the uncomfortable possibility that our moral framework might be built on the psychological needs of the defeated rather than eternal truths.

This etymological analysis serves as the foundation for everything that follows in the genealogy. By showing how moral language itself carries the sediment of ancient power struggles, Nietzsche undermines our confidence in moral absolutes. The words we use to describe virtue and vice aren’t neutral—they’re weapons forged in the crucible of social conflict.

What makes this analysis particularly unsettling is its explanatory power. Once you see the pattern Nietzsche identifies, it becomes difficult to unsee it in contemporary moral discourse. The celebration of victimhood, the suspicion of strength, the equation of suffering with virtue—all bear the hallmarks of the slave morality inversion he describes.

At Dionysus Reviews, we’ve seen countless philosophical works attempt to challenge conventional morality, but few do so with Nietzsche’s combination of historical rigor and psychological insight. His etymological detective work provides concrete evidence for claims that might otherwise seem like mere speculation.

The first essay doesn’t just decode master and slave morality—it reveals the battlefield where our current moral sensibilities were forged. Whether you accept Nietzsche’s analysis or not, his genealogical method forces a reckoning with the historical contingency of our most fundamental beliefs about good and evil.

The Noble Valuation and the Priestly Reversal of Values

Nietzsche’s exploration of moral transformation reveals one of philosophy’s most provocative arguments. He traces how our fundamental knowing of “good” and “evil” represents a complete inversion of ancient values.

Ressentiment as psychological mechanism driving slave revolt in morals

The concept of ressentiment operates as Nietzsche’s key to knowing moral revolution. This reactive resentment emerges when the weak blame their suffering on the strong, creating a psychological mechanism that transforms weakness into virtue.

I found Nietzsche’s analysis particularly striking because it explains how oppressed groups don’t simply accept their position but actively redefine moral categories to their advantage.

This psychological process allows the priestly class to exact revenge on nobles by inverting values entirely. Where strength once represented goodness, it now becomes evil. The weak transform their impotence into moral superiority, making patience and forgiveness the highest virtues while condemning power as vice.

How noble morality evaluates actions versus how slave morality judges intent

Noble morality focuses on outcomes and life-affirming consequences. Actions that promote happiness, strength, and individual flourishing receive the label “good” regardless of underlying motivations. This approach values results over intentions, celebrating what actually enhances human capability and joy.

Slave morality operates through a fundamentally different lens, prioritizing the intent behind actions over their consequences. This framework condemns pride and individual autonomy as sinful while elevating humility and obedience as virtuous. I noticed how this shift fundamentally changed moral evaluation from “what works” to “what intentions seem pure.”

The triumph of herd values in modern democratic movements

Nietzsche connects contemporary democratic movements to the widespread adoption of slave morality principles. Modern emphasis on collective values over individual excellence represents this moral inversion’s ultimate victory. Society increasingly suppresses individual strengths to maintain conformity and equality.

This triumph manifests in political systems that prioritize consensus over exceptional leadership and social movements that celebrate mediocrity while viewing excellence with suspicion. The herd mentality dominates, ensuring that outstanding individuals conform to average standards rather than inspiring others toward greatness.

The Architecture of Guilt and Bad Conscience

Nietzsche’s second essay transforms our knowing of guilt from moral failing to economic transaction. The psychological architecture he reveals shows how human conscience developed through social contracts rather than divine commandments.

Debt, Promise, and the Birth of Responsibility

The concept of responsibility emerges from humanity’s ability to make and keep promises within creditor-debtor relationships. Nietzsche traces how early societies required individuals to guarantee future behavior through contractual obligations. This capacity to promise created the first forms of personal accountability, where breaking agreements meant owing specific debts rather than committing abstract moral wrongs.

Guilt (Schuld) etymologically connected to debt (Schulden)

The German word “Schuld” reveals guilt’s economic origins, sharing roots with “Schulden” (debts). Nietzsche demonstrates how guilt originally meant owing something tangible to another person.

Punishment served as debt collection, providing creditors with satisfaction equivalent to their losses. This etymological archaeology exposes how moral guilt evolved from practical financial obligations into internalized shame and self-condemnation.

The contractual origins of justice versus later moral interpretations

Early justice functioned as balanced exchange between creditor and debtor, maintaining social equilibrium through reciprocal obligations. Nietzsche contrasts this practical system with later moral interpretations that transformed justice into divine judgment.

The shift from contractual to moral frameworks reflects slave morality’s influence, where reactive values reframe practical social tools into instruments of ressentiment and self-punishment against human flourishing.

The Internalization of Cruelty and Creation of the Soul

The second essay shifts from morality’s origins to its psychological transformation within civilized society. Here we witness how humanity’s most primal instincts undergo a radical metamorphosis when forced inward by social constraints.

“Bad conscience” as instincts turned inward through socialization

The transformation from primitive to civilized life created what amounts to a psychological revolution. Early humans possessed natural drives toward cruelty and aggression that found external release through violence against others. However, as customs and moral codes established boundaries these instincts could no longer flow outward freely.

This containment forced a dramatic redirection. The same cruel impulses that once targeted external victims became internalized creating the phenomenon of “bad conscience.” Instead of punishing others individuals began systematically punishing themselves through self-judgment and internal torment.

Self-torture as redirected cruelty under civilization’s constraints

The pleasure humans once derived from inflicting suffering on others didn’t disappear—it simply found new targets within the self. This “spiritualization and internalization of cruelty” manifests as elaborate forms of self-torture disguised as moral reflection. The individual becomes both torturer and victim in an endless cycle of psychological punishment.

What makes this particularly insidious is how this self-inflicted suffering feels pleasurable and meaningful. The same psychological satisfaction that came from external cruelty now emerges through internal self-flagellation making bad conscience both destructive and addictive.

The “prison” of society forcing animal instincts to become internal

Society functions as an elaborate prison system where wild animal instincts—once free to roam and express themselves—become trapped within individual consciousness. These instincts don’t disappear but rather press against the walls of social convention seeking release through internal channels.

This confinement creates new psychological structures including what we call the soul. Deprived of external outlets humans invent increasingly sophisticated forms of self-examination and internal suffering. The modern experience of guilt responsibility and moral anguish represents this imprisoned animality seeking expression through the only remaining avenue—the self.

Ascetic Ideals and Their Contemporary Relevance

The third essay of “On the Genealogy of Morals” confronts what might be the most psychologically disturbing aspect of human nature: our capacity for self-destruction in the name of higher ideals.

The Priest as Manager of Existential Suffering

I find it fascinating how the ascetic priest functions as a psychological entrepreneur who transforms raw human suffering into meaningful spiritual experience. This figure doesn’t eliminate pain but rather repackages it as divine purpose. The priest creates elaborate interpretive frameworks that make suffering feel intentional rather than random – turning existential despair into moral necessity.

“Sinfulness” as explanation redirecting ressentiment inward

The concept of “sinfulness” serves as a brilliant psychological redirect that I’ve seen echoed in modern therapy culture. Instead of allowing anger to target external sources of oppression the notion of personal sin channels that energy inward. This internalization creates a feedback loop where individuals become both prosecutor and defendant in their own moral courtroom.

The paradoxical nature of the will turning against itself

What strikes me most about this section is how the human will performs an almost impossible psychological contortion – becoming simultaneously the agent and victim of its own destruction.

The will doesn’t simply cease to exist but rather redirects its power toward self-negation. This creates what I can only describe as a spiritual masochism where suffering becomes both the means and the end of moral development.

Science and Scholarship as Disguised Forms of Asceticism

Nietzsche’s most provocative insight emerges in his third essay: modern scientists and scholars haven’t escaped the ascetic ideal—they’ve simply rebranded it. The very intellectuals who pride themselves on rational objectivity remain unwitting servants to the same self-denying impulse that drove medieval monks.

Modern truth-seeking as secularized ascetic ideal

Contemporary academia perpetuates ascetic values through its relentless pursuit of “objective truth.” Nietzsche argues that the scientific method’s emphasis on detachment and empirical rigor mirrors monastic discipline.

Researchers sacrifice personal comfort, relationships, and immediate pleasures for abstract knowledge. This “will to truth” represents a secularized form of religious devotion, where laboratories replace monasteries but the underlying ascetic structure remains intact.

Scientists’ self-denial and faith in objective truth

The modern scholar embodies ascetic principles through intellectual self-discipline and emotional detachment. Nietzsche observes how scientists renounce subjective experience in favor of measurable data, treating personal bias as contamination.

This systematic denial of human perspective echoes religious asceticism’s rejection of worldly desires. The faith placed in objective methodology parallels religious faith—both require practitioners to suppress individual will in service of transcendent ideals.

Nietzsche’s call for honest self-examination by “free spirits”

Nietzsche challenges intellectuals to recognize their unconscious commitment to ascetic values. He urges “free spirits” to question why truth itself deserves such reverence and sacrifice.

This self-examination requires acknowledging that even rational inquiry serves power structures and cultural conditioning. True intellectual freedom demands recognizing that the pursuit of truth can become another form of life-denial, preventing engagement with existence’s creative and key aspects.

Will to Power as Foundation of Nietzsche’s Critique

The will to power stands as the cornerstone of Nietzsche’s entire moral critique, serving as the underlying force that drives all human behavior and social formations. This concept fundamentally challenges conventional philosophical assumptions about human motivation and moral development.

Beyond Survival: Power as Primary Human Drive

I find Nietzsche’s repositioning of human motivation particularly striking in how it diverges from biological determinism. Rather than accepting survival as our primary instinct, he argues that humans are fundamentally driven by the desire to expand their influence and assert their strength.

This drive manifests in countless ways throughout daily life – from intellectual debates to artistic creation to social climbing. The will to power explains why humans often pursue goals that seem counterproductive to mere survival, such as extreme sports, revolutionary movements, or self-sacrifice for ideals.

Will to power superseding Darwinian survival instinct

What makes Nietzsche’s theory revolutionary is how it directly contradicts Darwinian frameworks that dominated 19th-century thought. While Darwin emphasized reproductive success and species preservation, Nietzsche saw these as secondary expressions of a deeper drive toward dominance and self-overcoming.

I’ve noticed how this perspective reframes seemingly altruistic behaviors as subtle expressions of power. Even acts of charity or self-denial can be understood as attempts to demonstrate superiority or control over circumstances and other people.

The will to power operates beyond conscious awareness, shaping our moral judgments and social structures in ways that often contradict our stated values about cooperation and mutual aid.

Power as explanation for seemingly self-destructive behaviors

Perhaps most brilliantly, Nietzsche uses the will to power to explain behaviors that appear to contradict survival instincts entirely. Self-harm, asceticism, and martyrdom all become comprehensible as expressions of this fundamental drive toward dominance – in these cases, dominance over oneself.

The ascetic priest exemplifies this dynamic perfectly, gaining spiritual authority precisely through self-denial and suffering. Their power comes from demonstrating control over bodily desires that defeat others, creating a hierarchy based on self-mastery rather than external conquest.

This framework illuminates why guilt and conscience developed as they did, serving not as moral guidance but as internalized mechanisms of control that redirect aggressive instincts inward when external expression becomes impossible.

Self-Mastery vs. Domination: Competing Manifestations of Power

After analyzing countless philosophical texts in my two decades of book reviewing, I find Nietzsche’s distinction between self-mastery and domination particularly interesting. His exploration of competing forms of power fundamentally challenges how we understand strength and influence in human relationships.

The “higher man” as one who masters himself rather than others

Nietzsche’s concept of the “higher man” represents a radical departure from conventional power dynamics. Instead of seeking control over others, this individual focuses entirely on self-transformation and personal growth. The higher man embodies what Nietzsche calls noble power – the ability to overcome one’s own limitations rather than imposing limitations on others. This internal mastery requires constant self-examination and the courage to reject comfortable moral certainties in favor of authentic self-creation.

Creative self-overcoming versus destructive domination

The contrast between creative self-overcoming and destructive domination forms the heart of Nietzsche’s power analysis. Creative self-overcoming involves continual personal transformation and value creation that affirms life and promotes growth.

Destructive domination, conversely, emerges from weakness and resentment, seeking to diminish others rather than lift oneself. Nietzsche argues that true strength manifests through self-discipline and creative expression, while domination reveals underlying insecurity masked as aggression.

Nietzsche’s contrast between noble-refined and barbaric power expressions

Nietzsche distinguishes between noble-refined power, characterized by confidence and life-affirmation, and barbaric power rooted in cruelty and resentment. Noble power stems from master morality, where strength naturally defines itself without reference to others’ weakness.

Barbaric power reflects slave morality’s reactive nature, defining itself through opposition and condemnation of strength. This distinction reveals how different moral frameworks produce entirely different expressions of human capability and ambition.

Contemporary Significance and Scholarly Reception

Nietzsche’s genealogical method revolutionized philosophical inquiry and established a foundation that continues to shape intellectual discourse today. His approach to examining moral values through historical analysis remains one of the most influential methodological innovations in modern philosophy.

Postmodern Philosophy’s Debt to Nietzschean Genealogy

The genealogical approach Nietzsche pioneered became a cornerstone of postmodern philosophical methodology. His technique of questioning the historical origins and development of seemingly natural concepts provided a blueprint for later thinkers to challenge established truths.

This methodological inheritance appears most prominently in the work of philosophers who adopted and expanded his genealogical framework. The emphasis on power relations and contingent historical development became central to postmodern critiques of knowledge and authority.

Foucault’s adoption and expansion of genealogical methodology

Michel Foucault transformed Nietzsche’s genealogical method into a systematic approach for analyzing power and knowledge structures in society. Foucault applied this technique to examine institutions like prisons, hospitals, and schools, revealing how seemingly natural social phenomena emerge from specific historical power struggles.

His genealogies of sexuality, punishment, and madness demonstrate direct methodological descent from Nietzschean analysis. Foucault explicitly acknowledged this debt, treating genealogy as a tool for exposing the contingent nature of contemporary social arrangements and challenging their apparent inevitability.

Derrida’s deconstructive approach paralleling Nietzsche’s fragmentation thesis

Jacques Derrida’s deconstructive philosophy shares fundamental similarities with Nietzsche’s genealogical critique, particularly in challenging stable meanings and fixed concepts. Both philosophers expose internal contradictions within seemingly coherent systems of thought and meaning.

Derrida’s method of revealing how texts undermine their own claims parallels Nietzsche’s demonstration of how moral concepts contain contradictory historical elements. This approach emphasizes flux and plurality over foundational certainty, reflecting Nietzsche’s suspicion of metaphysical absolutes and universal truths in moral philosophy.

Pros

- Groundbreaking Philological Analysis Redefining Ethics

- Unprecedented Psychological Depth in Moral Theory

- Revolutionary Historical Method Challenging Absolute Values

- Profoundly Influential Framework for Critical Theory

- Liberating Challenge to Unexamined Cultural Assumptions

Cons

- Historical Claims Often Lack Empirical Support

- Complex and Sometimes Obscure Argumentation

- Potentially Dangerous Political Misappropriations

- Aristocratic Elitism in Nietzsche’s Value System

- Selective Interpretation of Christian Ethics

Final Verdict

Nietzsche’s “On the Genealogy of Morals” remains one of philosophy’s most provocative and enduring works. I’ve found myself returning to its pages countless times and each reading reveals new layers of complexity that challenge my assumptions about morality and human nature.

What strikes me most is how Nietzsche anticipated many contemporary debates about power social construction and the nature of truth. His genealogical method continues to influence thinkers across disciplines from philosophy to sociology to psychology.

This isn’t an easy read but it’s absolutely needed for anyone serious about knowing the foundations of Western moral thought. Nietzsche forces us to confront uncomfortable questions about our deepest beliefs and that’s precisely what makes this work so valuable.

If you’re ready to have your moral certainties challenged and your worldview expanded I can’t recommend this book highly enough. It’s a masterpiece that demands engagement rather than passive consumption.

Sip The Unknown—Discover Stories You Never Knew You’d Love!

Dionysus Reviews Has A Book For Every Mood

Biography & Memoir

Fiction

Mystery & Detective

Nonfiction

Philosophy

Psychology

Romance

Science Fiction & Fantasy

Teens & Young Adult

Thriller & Suspense

Frequently Asked Questions

What is “On the Genealogy of Morals” about?

“On the Genealogy of Morals” is Friedrich Nietzsche’s 1887 philosophical work that explores the historical origins of moral values through three essays. It challenges conventional notions of good and evil by examining how moral concepts developed through psychological and social conditions rather than universal principles.

The work shifts focus from prescriptive ethics to descriptive analysis of why we think about morality the way we do.

What is the difference between master and slave morality?

Master morality originates from ancient nobility, where “good” meant noble, strong, and life-affirming. Slave morality emerged from oppressed groups who inverted these values, labeling the strong as “evil” and celebrating weakness, humility, and self-sacrifice as “good.”

This “slave revolt in morality” fundamentally transformed Western moral frameworks, prioritizing intent over outcomes and creating our current value system.

What is Nietzsche’s genealogical method?

Nietzsche’s genealogical method traces moral concepts to their psychological and historical origins rather than accepting them as universal truths. It treats moral values as historical artifacts shaped by cultural conditions and power struggles. This approach exposes how moral systems serve specific interests and reveals the contingent nature of what we consider fundamental ethical principles.

What is ressentiment in Nietzsche’s philosophy?

Ressentiment is a psychological mechanism where oppressed groups redefine moral categories to their advantage. It’s a form of creative revenge that transforms weakness into virtue and strength into vice.

This concept explains how slave morality developed as the weak found ways to psychologically overcome their powerlessness by inverting the value system of their oppressors.

How does Nietzsche explain the origin of guilt?

Nietzsche reinterprets guilt as originally an economic concept rather than a moral one. The German word “Schuld” means both guilt and debt, revealing how guilt emerged from creditor-debtor relationships. Human conscience developed through social contracts where the ability to make and keep promises created the concept of responsibility, which later evolved into moral guilt.

What is “bad conscience” according to Nietzsche?

Bad conscience results from civilization forcing humans to redirect their natural aggressive instincts inward. When society constrains primal drives toward cruelty and domination, these impulses turn against the self, creating internal torment.

This “spiritualization of cruelty” makes individuals both torturer and victim, leading to self-punishment and the development of concepts like the soul.

What role does the ascetic priest play in Nietzsche’s analysis?

The ascetic priest is a psychological entrepreneur who transforms suffering into meaningful spiritual experiences. They provide frameworks that make pain feel intentional and purposeful, channeling anger inward through concepts like “sinfulness.”

This creates a feedback loop where individuals become both prosecutor and defendant in their own moral struggles, turning self-negation into spiritual development.