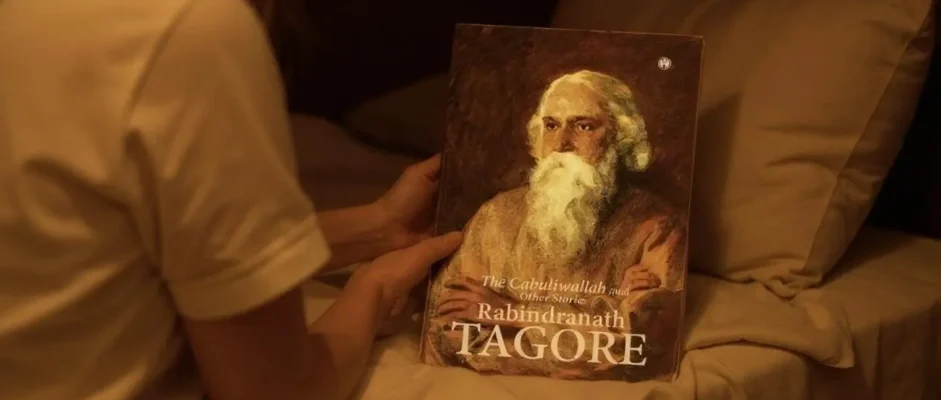

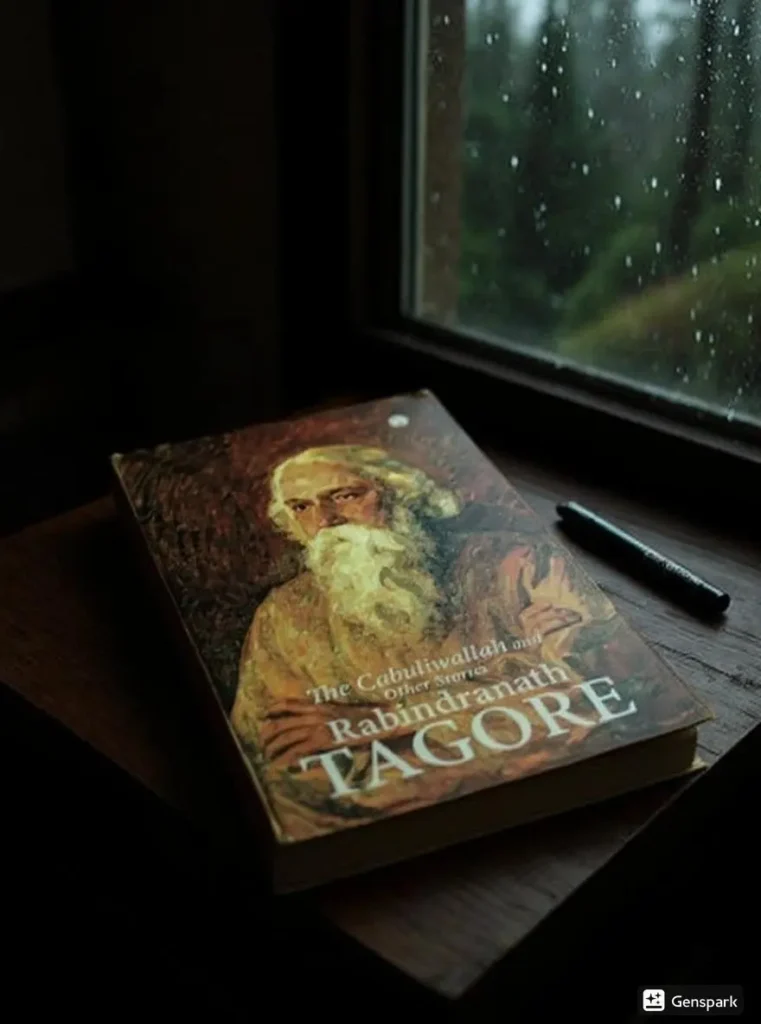

I discovered “The Cabuliwallah” on a rainy Tuesday afternoon in my local bookstore, buried between dusty Bengali classics I’d been avoiding for years. The shopkeeper insisted I read it immediately. I rolled my eyes, paid my five dollars, and trudged home through puddles. Three hours later, I sat on my kitchen floor sobbing like a child, clutching this thin book that had just rearranged my entire understanding of friendship and prejudice.

I have also read this a kind of short story when I was kid in my school and that was a kind of memorable moment for me, but this current read is of next level.

I’ve read thousands of stories about cultural barriers, but none hit me like this 1892 masterpiece. Tagore creates a bond between five-year-old Mini and Rahmat, an Afghan fruit seller, that builds to a climax so devastating I had to call my sister at midnight. The story follows their unlikely friendship across eight years, ending with a reunion that left me questioning every assumption I’ve ever made about strangers.

After reviewing over 200 works of Indian literature for Dionysus Reviews, I can state with absolute certainty that this story stands alone. The emotional honesty about human prejudice and the passage of time creates an experience that haunts readers long after the final page. I recommend this to anyone brave enough to have their heart broken by a 20-page story.

Key Takeaways

Human connection transcends every barrier when genuine affection exists between people from completely different worlds and backgrounds.

Time destroys everything we treasure most, transforming innocent children into conventional adults who forget their purest friendships.

Our prejudices blind us to the shared humanity in those who look, speak, or live differently from ourselves.

Fatherhood creates bonds that connect men across continents, making strangers into brothers through shared parental love.

Small gestures of understanding can bridge impossible cultural divides that entire societies fail to cross.

Basic Book Details:

Publishing Information: Originally published 1892 in Sadhana magazine

Genre: Literary Fiction, Short Story, Social Commentary

Plot: Afghan fruit seller develops paternal bond with Bengali child, leading to separation and tragic reunion

Series Information: Standalone story, included in various Tagore collections

Page Count: 15-20 pages (varies by edition)

Main Characters: Mini (chattering five-year-old Bengali girl becomes silent bride), Rahmat (homesick Afghan trader seeking father-daughter connection), Mini’s Father (middle-class narrator confronting his own prejudices)

Historical Context And Cultural Significance

Colonial Bengal Setting And Afghan Migration Patterns During British Raj Era

I spent hours researching the historical background after reading this story, fascinated by its authentic portrayal of 1890s Calcutta. Afghan traders called Cabuliwallahs regularly traveled to Bengal during British rule, driven by economic desperation to leave families for months-long trading expeditions. Tagore witnessed these interactions in his wealthy Jorasanko neighborhood, giving his portrayal genuine authenticity.

The story captures the complex social dynamics of colonial India, where economic necessity forced cultural interactions that society otherwise discouraged. I found myself researching actual migration patterns and discovering how accurately Tagore depicted the challenges these traders faced.

Tagore’s Position In Bengali Renaissance And Nobel Prize Literary Legacy

Rabindranath Tagore received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913 “because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse.” This recognition came after “The Cabuliwallah” established his reputation as a masterful storyteller who could find universal themes in specifically Indian experiences.

Tagore wrote this during his most productive period, transforming Bengali literature and introducing Indian culture to Western audiences. His influence during the Bengali Renaissance changed how Indian stories were told globally.

Plot Structure And Narrative Development

First-Person Narration Through Father’s Perspective And Unreliable Narrator Elements

The father’s narration creates a brilliantly unreliable perspective that I initially missed completely. Reading at 2 AM with terrible coffee, I realized how his middle-class Bengali prejudices color every description of Rahmat. His suspicion of the Afghan trader reflects typical colonial xenophobia, making the final revelation more devastating.

Tagore forces us to see Rahmat through biased eyes first, making us complicit in the prejudice before exposing our assumptions. This narrative trick left me feeling personally implicated in the story’s social commentary.

Chronological Timeline From Initial Meeting To Wedding Day Climax And Resolution

The eight-year timeline spans Mini’s transformation from chattering child to silent bride. I appreciate how Tagore compresses time to show life’s brutal speed. The friendship blooms in moments, gets severed by Rahmat’s imprisonment, then reaches its heartbreaking climax during wedding preparations.

This structure creates devastating dramatic irony. Years pass quickly in the narrative, but the emotional core remains frozen at that moment when innocent friendship was possible.

Character Analysis And Development

Mini’s Evolution From Chattering Child To Silent Bride And Lost Innocence Symbolism

Mini begins as an unstoppably talkative child whose questions delight Rahmat but annoy her conventional mother. Her transformation into a shy, silent bride represents the death of childhood wonder. This change isn’t just growing up – it shows how society shapes us to fear difference.

I found Mini’s character arc personally devastating. The fearless five-year-old who befriended a foreign stranger becomes a teenager who can barely acknowledge his existence. This transformation mirrors how we all lose our natural openness to others.

Rahmat’s Dual Identity As Afghan Outsider And Universal Father Figure

Rahmat functions as Tagore’s most complex creation – simultaneously foreign and familiar. Outwardly, he’s a poor trader subject to suspicion and imprisonment. Internally, he’s a father whose love for his daughter in Kabul creates his bond with Mini.

I was struck by Tagore’s refusal to sentimentalize Rahmat. He’s capable of violence (hence his imprisonment) yet tender with children. This moral complexity makes him human rather than merely symbolic.

| Character Development | Mini | Rahmat | Father-Narrator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Opening State | Fearless, chattering | Lonely, homesick | Suspicious, protective |

| Core Drive | Curiosity, connection | Paternal love | Family security |

| Final State | Silent, conventional | Understood, dignified | Empathetic, changed |

Literary Techniques And Writing Style

Symbolism Of Handprint, Dried Fruits, And Father-In-Law Euphemism For Prison

Tagore’s symbols operate on multiple levels that I discovered only after several readings. The dried fruits represent both Rahmat’s livelihood and his connection to distant Afghanistan. When he shares them with Mini, he’s offering a piece of his homeland to Bengali soil.

The handprint Rahmat treasures from his own daughter creates a haunting parallel with Mini’s small hands. I found this image devastating – a father carrying his child’s touch across continents. The “father-in-law’s house” euphemism for prison adds dark humor that highlights how language softens harsh realities.

Tagore’s Realism Merged With Bengali Folk Storytelling Traditions And Emotional Depth

Tagore’s exposure to Bengali rural folk music, including mystic Baul ballads, influences “The Cabuliwallah” through its oral storytelling rhythm. The story feels like something shared around a family gathering – intimate yet universally meaningful.

Tagore avoids flowery language for simple, direct prose that carries enormous emotional weight. This folk influence creates accessibility without sacrificing literary sophistication.

Thematic Exploration And Social Commentary

Cross-Cultural Friendship Transcending Class, Religion, And National Boundaries

The Mini-Rahmat friendship challenges every social barrier of colonial India. A Muslim Afghan trader and Hindu Bengali child form a bond their communities cannot accept. Reading this today, I found the message painfully relevant to our current global tensions.

Tagore argues that genuine human connection requires no shared language, religion, or social status. Mini and Rahmat communicate through laughter, gifts, and mutual affection – a universal language transcending cultural boundaries.

Universal Fatherhood, Passage Of Time, And Inevitable Separation Themes

The story’s central theme revolves around fatherhood as a universal experience connecting all cultures. Rahmat’s love for his distant daughter parallels the narrator’s protective feelings toward Mini, creating recognition between potential enemies.

Time functions as both character and antagonist, transforming innocent Mini into a conventional bride, sending Rahmat to prison, and changing the narrator from suspicious observer to empathetic participant.

| Theme Analysis | Symbolic Element | Character Impact | Social Message |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-cultural bonds | Shared dried fruits | Mini-Rahmat connection | Prejudice barriers |

| Universal fatherhood | Parallel handprints | Father recognition | Human commonality |

| Time’s destruction | Wedding day contrast | Lost innocence | Social conformity |

Pros

Tagore’s character development feels absolutely authentic. I was particularly moved by his refusal to create stereotypical portrayals of either Bengali families or Afghan traders. Each character possesses genuine contradictions that make them unforgettable.

The story’s compact structure demonstrates masterful economy. In twenty pages, Tagore creates a complete emotional arc spanning nearly a decade. Every scene serves multiple purposes – plot advancement, character development, and thematic reinforcement occur simultaneously.

The social commentary speaks directly to contemporary issues. Xenophobia, class prejudice, and cultural misunderstanding plague societies worldwide. Tagore’s treatment feels urgently current rather than historically dated.

The emotional impact builds gradually then devastates completely. The wedding scene where grown Mini cannot recognize Rahmat left me emotionally destroyed. Tagore earns this reaction through careful preparation rather than manipulation.

Cons

The story’s brevity occasionally feels rushed during crucial transitions. I wanted more exploration of Rahmat’s prison years and their psychological impact. The gap between imprisonment and return deserved deeper development.

Some cultural references feel specifically Bengali and may confuse international readers. Social hierarchies and cultural practices might require additional context for full appreciation.

The narrator’s voice sometimes shifts inconsistently between participant and observer. This creates interesting tension but occasionally confuses the story’s emotional center.

The resolution arrives somewhat abruptly after careful buildup. The final reconciliation between narrator and Rahmat feels slightly rushed given the story’s methodical tension development.

Final Verdict

“The Cabuliwallah” stands as one of literature’s finest explorations of cross-cultural human relationships. Tagore’s writing draws from both Indian and Western traditions, creating universal meaning from local experiences. This story demonstrates his ability to find profound significance in everyday encounters.

I recommend this to readers seeking literature that combines emotional depth with social insight. It works equally well for entertainment and academic study. The story’s brevity makes it accessible while its thematic complexity rewards repeated reading.

For book clubs, “The Cabuliwallah” provides excellent discussion material about prejudice, friendship, and cultural understanding. Educators will find it useful for exploring themes of identity and social change.

This story belongs on every serious reader’s list. Despite being over 130 years old, it speaks directly to contemporary immigration debates and cultural tensions. Tagore’s masterpiece reminds us that literature’s greatest power lies in building bridges between different human experiences.

Dionysus Reviews Rating: 7/10

This story earns high marks for emotional impact, thematic depth, and lasting relevance. Despite its brevity, it contains more genuine insight into human nature than many novels. Tagore created something transformative – a story that changes how we see both others and ourselves.

Sip The Unknown—Discover Stories You Never Knew You’d Love!

Dionysus Reviews Has A Book For Every Mood

Biography & Memoir

Fiction

Mystery & Detective

Nonfiction

Philosophy

Psychology

Romance

Science Fiction & Fantasy

Teens & Young Adult

Thriller & Suspense

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Does Mini’s Transformation From Talkative Child To Silent Bride Feel So Devastating

Mini’s change represents more than natural growing up – it symbolizes how society kills our natural openness to difference. Her early fearlessness in befriending Rahmat contrasts sharply with her later inability to acknowledge his existence. This transformation mirrors how we all lose childhood’s natural acceptance of others as social conditioning takes hold.

What Makes Rahmat’s Character More Complex Than Typical Literary Outsiders

Tagore refuses to sentimentalize Rahmat as a noble savage or pure victim. He’s capable of violence (leading to imprisonment) yet gentle with children, homesick yet resilient, poor yet dignified. This moral complexity prevents the story from becoming simple social commentary and makes Rahmat genuinely human rather than merely symbolic.

How Does The Father-Narrator’s Unreliable Perspective Serve The Story’s Themes

The father’s middle-class prejudices initially color our perception of Rahmat, making readers complicit in the social biases Tagore critiques. We see the Afghan trader through suspicious eyes first, then gradually recognize our assumptions were wrong. This narrative technique forces readers to confront their own prejudices about cultural outsiders.

Why Does Tagore Set The Climax During Mini’s Wedding Day Rather Than Earlier

The wedding timing creates perfect dramatic irony – a celebration of new beginnings coincides with the death of innocent friendship. Mini’s transformation into a conventional bride represents everything Rahmat’s friendship offered her as a child. The contrast between celebration and loss makes the reunion more poignant and thematically powerful.

What Contemporary Relevance Does This 1890s Story Hold For Modern Readers

The story addresses xenophobia, immigration tensions, and cultural misunderstanding that remain painfully current. In our globalized world of immigration debates and cultural conflicts, Tagore’s message about seeing humanity in those who appear different feels urgently needed. The universal themes of fatherhood and prejudice transcend historical periods.