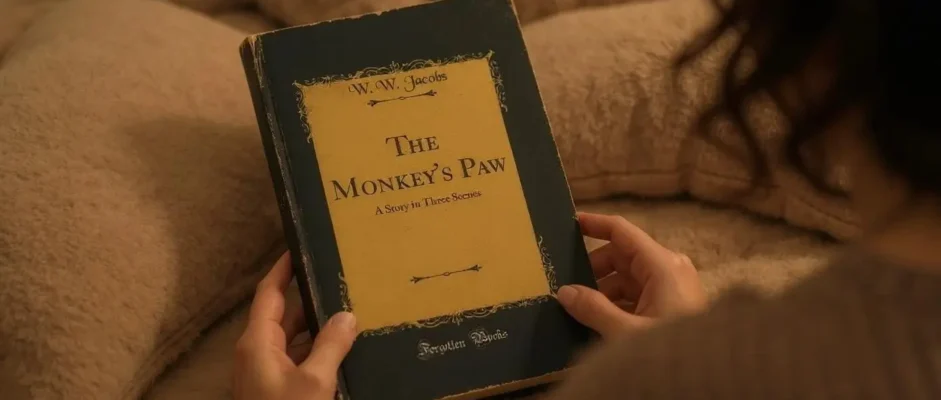

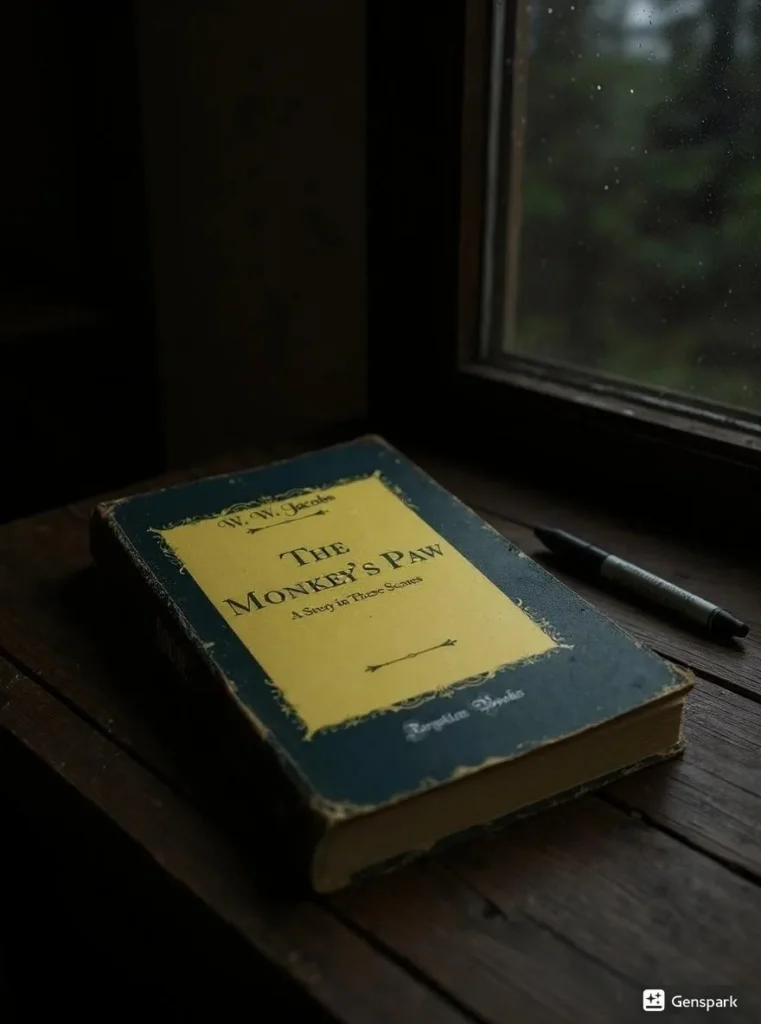

I slammed this slim volume shut at 2:47 AM, my coffee gone cold, heart hammering against my ribs. I had picked up “The Monkey’s Paw” during a January blizzard, thinking I’d breeze through another Victorian tale before bed. Instead, I found myself checking every shadow in my apartment, texting my roommate to make sure she was okay. This story grabbed me by the throat and refused to let go.

I’ve devoured horror fiction for two decades. I’ve survived Stephen King marathons and Lovecraft binges. But W.W. Jacobs crafted something different here – psychological terror that burrows into your brain and sets up permanent residence. I caught myself staring at my own hands afterward, wondering what I might wish for if given the chance, then immediately pushing the thought away.

Reading this story taught me that the most effective horror doesn’t come from monsters or gore. It comes from our own desires turned against us. Jacobs understood that we are our own worst enemies, and he built a perfect trap to prove it.

Key Takeaways

Suggestion creates more lasting fear than explicit description – I found myself imagining horrors far worse than anything Jacobs could have written.

Wish-fulfillment fantasies carry deadly consequences when they ignore reality’s complex web of cause and effect.

Victorian horror fiction excelled at exploring social fears through supernatural metaphors that remain relevant today.

Family relationships become most authentic when tested by impossible choices and moral dilemmas.

Short story structure achieves maximum emotional impact when every single word serves both plot and theme.

Basic Book Details

Publishing Information: September 1902 by Harper’s Monthly Magazine, later included in “The Lady of the Barge” collection

Genre: Victorian Horror, Gothic Fiction, Supernatural Short Story

Plot: A family receives a magical monkey’s paw that grants three wishes, but each wish comes with devastating unintended consequences

Series Information: Standalone short story, part of “The Lady of the Barge” collection

Page Count: Approximately 15-32 pages (varies by edition)

Main Characters:

- Mr. White: A cautious father whose curiosity overrides his better judgment

- Mrs. White: A loving mother whose grief drives her to desperate measures

- Herbert White: The couple’s son whose playful skepticism masks deeper wisdom

- Sergeant-Major Morris: A weathered soldier who serves as both tempter and warner

Story Analysis and Impact

W.W. Jacobs was born September 8, 1863, in London, where his father managed a Thames wharf. This maritime background infuses his fiction with exotic elements and sailor’s tales that feel authentic rather than manufactured. I could smell the fog and hear the Thames lapping against the docks as I read.

The story emerged during Britain’s imperial peak, when exotic artifacts flooded middle-class homes. Jacobs uses this colonial backdrop brilliantly – the paw originates from India, representing cultural appropriation’s dangerous allure. I noticed how he makes the sacred object feel simultaneously fascinating and repulsive.

The White family represents emerging middle-class comfort mixed with restless ambition. Their cozy parlor becomes a battleground between domestic security and dangerous desire. I recognized my own family’s dinner table conversations in their casual discussions of money and dreams.

Jacobs constructs his tale in three precise acts, each corresponding to one wish. The mathematical precision amazed me. Every element serves multiple purposes – Morris’s reluctance plants doubt, Herbert’s jokes prove prophetic, the chess game establishes themes of strategy and unintended moves.

The first wish for £200 seems reasonable, almost responsible. This made the family’s decision feel justified, which makes the horrific fulfillment more devastating. I found myself thinking, “I would have done the same thing,” which made the tragedy personal.

Herbert’s factory death hits harder because Jacobs refuses graphic detail. Instead, he focuses on the parents’ emotional devastation and the cruel irony of receiving exactly the money they wished for as compensation. I felt sick reading about the company representative’s awkward visit.

The final act pushes horror to its logical conclusion. Mrs. White’s desperate wish to resurrect Herbert creates the story’s most terrifying moment – not through showing us the returned son, but through Mr. White’s absolute terror at what might be waiting outside. I held my breath during the knocking sequence, even on my third reading.

Character Psychology and Family Dynamics

The Whites feel real in their flaws and contradictions. Mr. White embodies middle-class aspiration – comfortable but yearning for more, practical yet susceptible to temptation. I recognized my own father in his cautious optimism.

Mrs. White transforms from skeptic to believer to desperate mother willing to risk everything. Her journey represents maternal love pushed past reason’s boundaries. I found her final scenes heartbreaking in their portrayal of grief overwhelming logic.

Herbert serves as the story’s voice of reason while treating the paw as entertainment. His playful mockery – “If you only cleared the house, you’d be quite happy, wouldn’t you?” – proves tragically prophetic. His death gains power from his earlier skepticism and youth.

Sergeant-Major Morris functions as more than a plot device. He’s haunted by his own experience with the paw, struggling between warning others and his inability to explain the full danger. His drinking suggests someone trying to forget trauma. When he attempts to burn the paw, we see a man protecting others from his mistakes.

Literary Techniques That Create Terror

Jacobs plants clues throughout that reward careful readers while maintaining suspense. Morris’s warnings, Herbert’s jokes, even the opening chess game’s themes – all prepare us for tragedy while feeling natural and unforced.

The £200 sum becomes particularly effective foreshadowing. Only afterward do we realize how perfectly this amount aligns with typical industrial accident compensation, suggesting the paw orchestrates tragedies rather than granting wishes.

Dramatic irony permeates the narrative. We understand danger before the characters do, creating tension between knowledge and willful ignorance. This technique makes us complicit – we want to warn them while being drawn into the story’s dark logic.

The monkey’s paw operates on multiple symbolic levels. As a severed body part, it represents death and mutilation. As an exotic artifact, it symbolizes cultural appropriation. As a wish-granter, it embodies dangerous shortcuts to complex problems.

Fire imagery recurs throughout – the cozy hearth, Morris’s burning attempt, the flames that consume the paw. Fire represents both comfort and destruction, mirroring human desires’ dual nature.

Performance as Horror Fiction

Comparing “The Monkey’s Paw” to other Victorian horror reveals its unique position. Unlike Bram Stoker’s elaborate Gothic machinery or Arthur Machen’s cosmic horror, Jacobs created intimate, domestic terror that feels psychologically realistic.

This restraint distinguishes it from contemporaries who relied on supernatural spectacle. Where Dracula requires extensive mythology and Jekyll and Hyde needs scientific explanation, “The Monkey’s Paw” operates through pure suggestion and human psychology.

Contemporary horror writers from Stephen King to Thomas Ligotti acknowledge Jacobs’ influence. King’s “Pet Sematary” directly echoes this story’s exploration of parental grief and resurrection’s temptation. Both understand that family love can drive us to destroy what we’re trying to protect.

Reader Experience and Accessibility

The story works on multiple levels simultaneously. As entertainment, it delivers genuine chills across multiple readings. As social commentary, it offers insights into Victorian anxieties that remain relevant. As literary art, it demonstrates masterful language, structure, and theme control.

I recommend this story to readers interested in horror fiction’s evolution, the relationship between Victorian literature and social anxiety, and short story craft mastery. It’s also necessary reading for understanding how suggestion creates more powerful effects than explicit description.

The story’s brevity contributes to its impact while limiting character development. The Whites remain somewhat archetypal despite their psychological authenticity. This represents my only significant criticism – I wanted deeper exploration of their relationships and histories.

For contemporary readers, this story offers a masterclass in efficient storytelling and psychological horror. It demonstrates how effective terror emerges from recognizable human emotions rather than exotic supernatural creatures.

Final Verdict

“The Monkey’s Paw” represents horror fiction at its most refined and effective. This isn’t shock value or graphic violence – it’s psychological terror through suggestion, character development, and thematic depth.

The story’s genius lies in exploring the gap between what we want and what we need. Jacobs understood that effective horror comes from our desires turned against us. The White family’s tragedy emerges from their own understandable wishes – financial security, family reunion, peace from suffering.

I give this story high marks for perfect execution of psychological horror, masterful suggestion over explicit description, and themes that remain powerfully relevant. While brevity limits character development, the story achieves maximum impact through precise craftsmanship and restraint.

Reading “The Monkey’s Paw” taught me that the best horror serves as a mirror, reflecting our potential for self-destruction through seemingly innocent choices. This lesson continues resonating every time I encounter wish-fulfillment stories in contemporary culture.

Dionysus Reviews Ratings: 7.5/10

This story earns high rating through perfect psychological horror execution, masterful restraint, and timeless themes. It’s horror fiction at its most sophisticated and effective.

Sip The Unknown—Discover Stories You Never Knew You’d Love!

Dionysus Reviews Has A Book For Every Mood

Biography & Memoir

Fiction

Mystery & Detective

Nonfiction

Philosophy

Psychology

Romance

Science Fiction & Fantasy

Teens & Young Adult

Thriller & Suspense

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does Sergeant-Major Morris try to burn the monkey’s paw if he knows it grants wishes?

Morris attempts to destroy the paw because he’s experienced its true nature firsthand. His three wishes apparently brought him such trauma that he drinks heavily and can barely discuss the experience.

He understands that the paw doesn’t grant wishes benevolently – it orchestrates tragedies that technically fulfill requests while destroying lives. His burning attempt represents a desperate effort to protect others from his own mistakes.

What exactly happens to Herbert White at the machinery works?

Jacobs deliberately keeps Herbert’s death vague, mentioning only that he was “caught in the machinery” and that his body was so mangled it could barely be identified. This ambiguity serves the story’s psychological horror approach – our imagination creates something far worse than explicit description could achieve. The £200 compensation suggests a typical industrial accident of the era.

Does Mrs. White actually succeed in bringing Herbert back from the dead with her second wish?

The story strongly implies that something does return when Mrs. White wishes for Herbert’s resurrection. The increasingly desperate knocking at the door, Mr. White’s absolute terror, and his frantic search for the paw to make his third wish all suggest that her wish worked – but that what returned was not the Herbert they remembered.

The ten-day gap between death and resurrection implies decomposition that would make the returned Herbert horrific.

What is Mr. White’s third and final wish?

Though never explicitly stated, Mr. White’s third wish is clearly for whatever is knocking at their door to go away or return to death. His desperate scrambling to find the paw while his wife struggles with the door locks, followed by the immediate cessation of knocking when he makes the wish, confirms that he used his final wish to undo his wife’s resurrection request.

Why does the monkey’s paw have exactly three wishes, and why does it look the way it does?

The three-wish structure comes from traditional folklore and fairy tale patterns, but Jacobs uses it to create perfect dramatic progression – setup, consequences, and resolution. The paw’s mummified appearance reflects its origin as a sacred object that has been corrupted and commodified.

Its dried, claw-like form makes it inherently repulsive while suggesting death and decay, preparing readers for the story’s themes about the dangers of trying to cheat death and natural order.